Our dad, Patrick Hill Rupertus, was a Marine aviator, Vietnam veteran and son of Marine Major General William H. Rupertus, who I have written about extensively in our book, Old Breed General.

Lately, as I’ve been watching Vietnam: The War That Changed America on Apple TV and reflecting on the anniversary of our fathers’ passing from Agent Orange-related cancer (March 6, 1991), I felt compelled to share this story.

This is for him—the general’s son, our beloved father.

Our father, Pat Rupertus came into this world in the shadow of history—born in Washington, DC, on August 18, 1939. At this time, his father commanded the Marine Barracks at 8th and I Streets. He entered a life steeped in military tradition, one that would bring both honor and heartbreak.

The historic brick buildings that housed the Marine Corps’ most cherished traditions would later become the site of unimaginable grief.

In 1942, when Dad was just three years old, his father, who had been with the Marine Corps since 1913, joined the 1st Marine Division as assistant division commander (ADC) to fight the Japanese in the Pacific. By 1943, he was division commander.

General Rupertus came home from the Pacific in November 1944, and was head of Marine Corps Schools at Quantico where Dad and his mom (Sleepy) joined him in the officers quarters. Video shows he took Dad all around Quantico, on horses, planes and tanks. And on a cold January day in 1945, video shows our family and friends coming to town for a big ceremony for his Distinguished Service Medal.

ou can view this video here: https://youtu.be/dZ3svI_C3z0?si=e7GZZvYdIvbOxbUb

Three months later, as the Marines had their victory on Iwo Jima, tragedy struck with brutal swiftness. During a 1st Marine Division Veterans’ party at the Marine Barracks in Washington, DC, Dad’ father, Major General Rupertus, suffered a heart attack and collapsed on the steps of Col. Kilmartin’s house, his former chief of staff in the Pacific.

Our grandmother, Sleepy, only 34 years old, ran to him in a well of tears, cradling her husband as he took his last breath.

In the aftermath of this sudden and devastating loss, Sleepy and young Pat had to quickly rebuild their lives. They carefully packed up their belongings for the move from Quantico to Washington, DC. She ensured they preserved all of her husbands uniforms and military memorabilia—precious artifacts of his distinguished service from 1907 to 1945, including many condolence letters. Much of what we have today in our family trunks and library.

Their saving grace came through the unwavering support of Tom and Edythe Hill, whose friendship with General Rupertus dated back to Washington, DC and their shared time in the Marine Corps.

The Hills had stood by General Rupertus during his darkest hour when he lost his first family to Scarlet Fever while they were all stationed with the 4th Marines at the Peking Legation in Peking, China (1929-1931), and now they stood ready to help his second wife, Sleepy and son Pat, in 1945.

They helped Sleepy and our Dad find refuge in McLean Gardens, a residential community in northwest Washington, DC. Here, amid the post-war housing development’s brick buildings and tree-lined streets, Sleepy took a job and worked to create a new normal.

Dad attended nearby Sidwell Friends School before moving on to Landon School in Bethesda, where he boarded. At Landon, he found solace in football and forged friendships that would last a lifetime. But fate wasn’t finished testing his resilience. During his high school years, Sleepy succumbed to an aggressive, three-month battle with leukemia, dying at age 43.

At sixteen, Dad was left without his parents.

Sleepy’s sister, Josephine Hill Carter, became a second mother to our Dad, embracing him as one of her own children and providing the loving stability he desperately needed. And so did his father’s Marine friends who served with General Rupertus in the Pacific.

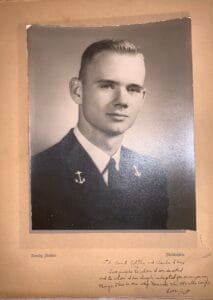

Grief found Dad, but it never broke him. Instead, he set his sights on the United States Naval Academy—an institution that had been part of his family’s legacy since 1922.

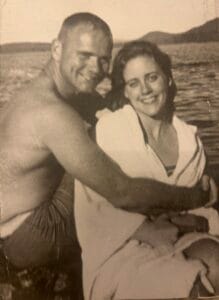

Despite repeating his plebe year, to the shock of one of his close friends who dropped out, his characteristic grit and determination carried him through to graduation in 1962. That same year, he married our beautiful mother, Gail Bennett, before embarking on his journey to flight school.

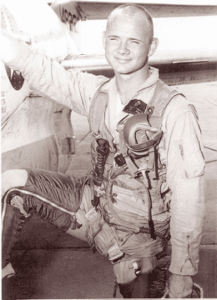

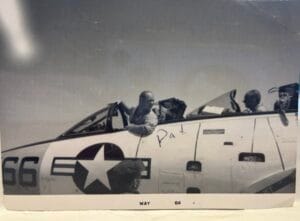

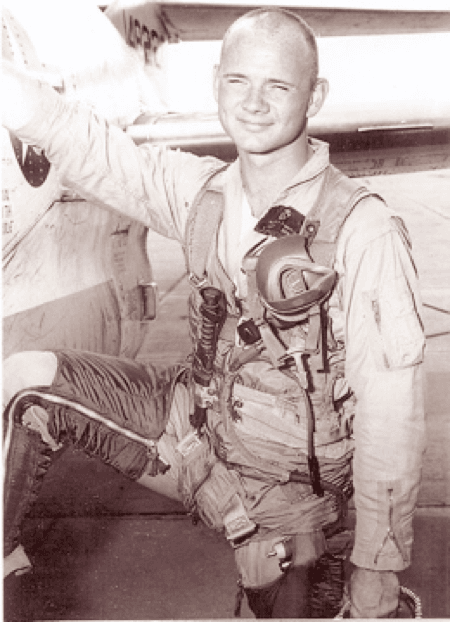

As a Marine aviator, Dad flew A-4 Skyhawks from aircraft carriers and completed two tours in Vietnam, earning citations for his bravery in supporting his fellow Marines. His squadron, VMA 332, nicknamed him “Mr. Clean”—a moniker that spoke to to his similar look to the image of the man for the Mr. Clean brand.

My understanding is Dad spent a lot of time in Chu Lai, Vietnam. He was an aviator also a Forward Air Controller.

Dad carried his early losses quietly, rarely speaking about his parents, his Naval Academy years, or his time in the Vietnam War. Only later, as I researched our grandfather’s story for my book Old Breed General, did I fully grasp the weight my father carried. He had built his life not just on resilience—choosing to honor the past by forging ahead, even when grief threatened to hold him back.

Through my father’s journey—from the loss of his parents, to a Naval Academy graduate, from Vietnam veteran to loving husband, and father—he embodied the Marine spirit his own father had instilled: unwavering determination in the face of adversity – and a love of family. The military memorabilia he and Sleepy had so carefully preserved would later help tell not just General Rupertus’s story, but open my eyes to Dad’s own story.

A Daughter’s Memories

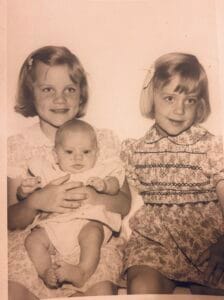

The military had shaped our family’s entire geography: Heather was born at Kingsville Naval Air Station in Texas, Kimberly in Bryn Mawr while Dad was deployed in Vietnam, and me (a surprise) in Pittsburgh, after he joined the reserves and was working at Westinghouse as an engineer.

We moved through Chicago, where Dad transitioned to life insurance, until 1980, when the sudden passing of a close friend and client made him reevaluate his path. A “What Color is Your Parachute” weekend inspired him to pivot from insurance to real estate development—something he’d always dreamed of.

That year, he moved us to McLean, Virginia, closer to his Washington, DC roots. It was a massive change that seemed to help Dad—and all of us—thrive and reconnect.

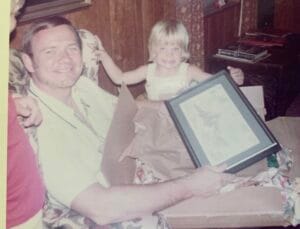

As the youngest daughter, I spent a lot of time with Dad while Mom worked in real estate on weekends and my sisters were with their friends or working. We were buddies. He played guitar for me. He took me to the bakery to get those giant yellow smiley cookies. He took me shopping for clothes, and even to his barber for my haircuts. He was strict—sometimes scary strict—and he disciplined me when I needed it. Though, according to my sisters, I got off easy.

We were not supposed to watch TV during the weekdays or get phone calls past seven pm. Of course my sisters and I snuck in some TV time. But, if Dad came home early from work and he thought we had been watching TV, he’d go over to the TV and place his hand on it. If it was still warm to his hand…

Run!

Dad pushed us to work hard, stay humble, and laugh at ourselves. He would always say “Don’t take a lazy man’s load,” as we girls were raking mounds and mounds of leaves in the Fall or carrying grocery bags.

Good or bad, I always felt deeply connected to his emotions, as if they were my own. He used to joke how sensitive I was. Wonder why? If you grew up with a military parent, especially a Marine, you understand: sometimes you walk on eggshells.

We also resembled each other. Sometimes, he would grab my square jaw, look into my eyes, and say, “Ahh, it’s just like looking in the mirror,” and “If Sampson had a jaw like yours he could have slayed another 1000 Philistines.”

Life in McLean was filled with family, tradition, and reunions. Weekends were spent with his mother’s sisters and their husbands: Aunt Jo and Uncle Bev, Aunt Dixie and Uncle Steve (both men had attended the Naval Academy, and served with the Navy in the Pacific during WWII).

We were now also closer to our grandparents, and more family and cousins on my Mom’s side. Great move, Dad. the ,one was a win-win-win.

His Naval Academy Class of 1962 reunions became regular events, and we went to magical evening parades at the Marine Barracks at 8th and I. I can still see those Marines at the evening parades—immaculate in their uniforms, executing rifle drills with perfect precision in DC’s sweltering summer heat. The rhythmic clatter of rifles, the sharp snap of dress shoes against pavement, the hushed reverence of the crowd—those nights felt almost sacred.

In the background, though, Vietnam still lingered, especially when it came to the big screen. In the 1970s and 80s, as movies about Vietnam started to emerge, I had the opportunity to watch some of them with my father, this USMC Aviator and Vietnam veteran.

Films like “The Deer Hunter,” “Apocalypse Now,” “The Great Santini,” “Top Gun.” Deer Hunter. When Top Gun came out in May 1986, we went to the movie with our Dad. During flying scenes, he’d light up, arms swooping through the air, demonstrating flight patterns right there in the theater. As a teenager, I’d slide down in my seat, mortified.

Now, those memories make me smile.

But Platoon, which came out in December, 1986 was different. Dad never flinched at war movies—until Platoon. He hesitated, unsure if he wanted to see Oliver Stone’s unfiltered portrayal of Vietnam. But one Saturday, he suddenly decided to go—and wanted me by his side. I sensed he needed company. The movie was tough to watch, and the drive home was quiet, heavy with unspoken emotions. And, at age 16, I never asked him what he thought about the movie.

Sometimes, there are no words. Looking back, I realize that silence was its own kind of story.

The Vietnam Veterans Wall

A delicate silence had also surrounded the Vietnam Veterans Memorial when it was completed four years earlier in November 1982. Maya Lin’s design and the overall idea of the wall had sparked controversy, though I couldn’t understand why. How could honoring those who served, died, and went missing be divisive?

The dedication was set for November 13, 1982 with an unveiling and a parade of veterans. When Dad said we should go, my sister Kimberly and I joined him on that gray, cold November day. I imagined a quick outing from McLean—take the George Washington Parkway to Pennsylvania Avenue, see the wall, then get back to my friends.

But time seemed to slow as we drove. Even the Potomac River appeared to move in slow motion, the atmosphere dense with something I couldn’t name.

When we arrived near the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, I expected crowds, bands warming up, the kind of excitement that usually surrounds events in Washington, DC. Instead, there was silence. Parking was easy. The rain had started to mist.

We were drawn to the glow of a lantern inside an old brown canvas tent, where solemn veterans stood watch over a table covered with POW/MIA information. They weren’t there to distribute parade guides. They were there for those who didn’t make it home.

As we walked toward the wall, the hush deepened. People knelt, searching for names, crying when they found them, pressing their cheeks against the smooth stone as if making a long-lost connection. Some bent their foreheads against it in prayer, while others traced names onto paper, preserving the memory of loved ones.

Dad walked back and forth in a trance, silently taking it all in. His striking light blue Irish eyes were red-rimmed, his brow furrowed. No jokes, no laughter, no smiles—not today.

I wanted to hug him but was afraid to interrupt his silence. He seemed so far away. I wonder now—was he back in Vietnam, watching a friend die? Calling in support for troops under fire? Flying his A-4 over dense jungle? Remembering landing on an aircraft carrier in the middle of a storm? Or, remembering all this, and the unwelcome home?

The Vietnam Veterans Parade

The parade that passed before us defied everything I knew about parades in our nation’s capital. No blaring horns split the air, no bands, no drums thundered down Pennsylvania Avenue. The familiar sights were absent—no majorettes twirling in the sun, no politicians’ practiced waves from convertibles, no children diving for candy thrown from floats.

Instead, a battalion of Vietnam Veterans marched. They came from every race and background, unified by their shared experience, many still wearing their old green fatigues. Some carried company flags, others the American flag. Though most seemed to be in their late 30s and 40s, their faces carried the weight of decades.

Even as a young girl, I could see how grief had aged them beyond their years. Yet in their unified march, I glimpsed something else—a quiet strength forged in fire.

History frames the Vietnam War as a Cold War chess piece, a stand against communism after France’s failed occupation. Our military answered the call, fighting in a conflict that our own leaders struggled to define. The cost was devastating. Some never returned, and those that did were haunted by the memory of war—and that shameful unwelcome home.

Others, like our family friend Air Force aviator Quincy Collins, endured seven years of brutal captivity alongside Senator John McCain in the Hanoi Hilton.

Back home, the nation fractured. When actress Jane Fonda visited Hanoi, she turned her back on our American POWs. Returning soldiers faced contempt—denied cab rides, spat upon, with Black veterans bearing even harsher treatment. Protests grew, clashed—until gunfire at Kent State left four students dead. The nation bled from self-inflicted wounds.

They didn’t seem to openly call it PTSD back then—that fog that settled over the 1970s and ’80s. But that’s what gripped so many Vietnam veterans and the families who loved them—a weight of unresolved grief that refused to lift. Those icicles inside.

We did not treat our Vietnam vets well.

That’s a hard truth we must learn. But this black wall, with its sharp angles cutting through the November mist, began to slice through decades of that shit. That hazy, suffocating PTSD fog.

The monument is now a loyal guardian for our Vietnam veterans. It made an unshakable statement: We honor those who sacrificed for our country.

Warriors, their memories, may have softened with time, but the smells, feelings, sights, sounds, and losses remained etched in their soul. Today, after watching our military endure multiple tours in the Middle East, we better understand the invisible wounds of war. We’re learning, finally, to recognize and support those who carry these scars.

But for those without a connection to the military, the bone-deep camaraderie and unwavering commitment to service over self, and etched in memories, might always remain a mystery.

Dad used to joke with my sisters and me about being “God Damned Civilians”—whether he picked that up from the Marine Corps or The Great Santini movie, I’ll never know. But now, I wonder: Could we GDCs ever truly understand the sacrifice these men and women make to protect our right to live, work, worship, and yes, even protest in peace?

Our father never defined himself as a Vietnam veteran. But how would I know? He never spoke about it to me. And, I never asked him. Nor did he seemed depressed – more a trusted friend with a great sense of humor. Yet I now know, he carried a lifetime of memories too profound for words.

On that gray November day in 1982, as the parade marched past and veterans shouted for Dad to join them, something began to heal—not just for him, but for all of us who loved these warriors enough to stand with them in their silence.

The First Signs

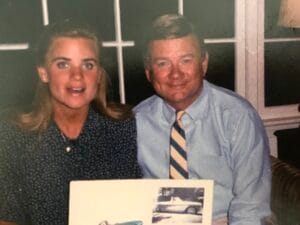

At 49, Dad still had a great sense of humor, was happy and had a strong presence in our lives. He and Mom were loving their new chapter as empty nesters, and I cherished our time together when I visited from college.

One autumn afternoon during my break from the University of Georgia, something changed. My favorite ritual with Dad was biking the W&OD Trail in Virginia—his competitive spirit always on display. He’d race ahead, blue eyes gleaming, legs still strong and muscular, leaving me trailing behind no matter how fast I was. He did the same thing if we were running – sprinting past me.

That day, as dusk settled in, I raced ahead on my bike, expecting his usual playful ambush. When I glanced back, he was far behind. I stopped at a crosswalk, watching him approach—slowly.

“Hey, Daddy, you okay?”

“I’m fine,” he said. “Just had to slow down a bit. My hip’s been bothering me for a few weeks.”

“Have you seen a doctor?”

“Not yet. I’ll check it out when you go back to UGA. Just don’t tell your mom, okay?”

That request haunted me later. They never kept secrets from each other. Those two were lovebirds. But I went back to Athens, swept up in soccer and college life, barely thinking about his hip pain.

The Diagnosis

When I came home for Christmas break that sophomore year, I was happy to be back in our cozy and bright home with my parents and ready to visit my high school friends. Yet Dad called me into the living room almost as soon as I had dropped my bags in my bedroom.

Hmm, I ran downstairs and sat near him on the sofa, smiling. My mind raced through possible college transgressions. Nothing could have prepared me for his words.

“Amy… I have cancer.”

Whoa. What? Oh my God. Talk to me.

My lungs burned. Tears blurred my vision.

Agent Orange-related lung cancer, the doctors said it is another cruel legacy of the Vietnam War, claiming its veterans decades later.

The Final Months

By that summer of 1990, Mom sought solace in painting and played Chopin on the piano, her fingers soaring across the keys as she faced the uncertain path ahead. Mom loved Dad with every fiber of her being – a love so deep it made the impending loss almost unbearable.

Dad was thinner, but his spirit remained unbroken, his bright sweaters a defiant flame against his fading frame. Even with a chemo pump tethered to his body like an unwelcome companion, he refused to be grounded, returning to the skies he loved as pilot. Some days, he’d appear like a vision in the halls of the U.S. Senate where I was interning, his brave smile trying to preserve our last fragments of normalcy.

But by January 1991, when I left for school after Christmas break with a cold, he ended up in the hospital with pneumonia. His lungs, once strong enough to carry him through the heavens, now betrayed him, filling with fluid.

Damn cancer. Damn it to hell.

A month later, Mom’s February call pierced my heart – she said I needed to come home.

She already booked my flight. The urgency in her voice told me everything words couldn’t. My boyfriend (now my husband) raced me down Atlanta Highway to Atlanta Airport in his black Scirocco, the world blurring past as I braced myself for what awaited – a journey straight into the darkest storm clouds of grief.

At home, Dad lay propped up in their bed, a shadow of his commanding presence. I embraced him, fighting back tears as I massaged his feet like I had so many times before.

My sisters gathered, and we maintained our vigil with our Mom, clinging to every precious moment. As Mom’s piano echoed through sleepless nights, the angels of the Visiting Nurses team drifted in and out. Grief took over until I could barely breathe, until Dad’s doctor prescribed anti-anxiety medication to dull the pain of loss.

Dad’s final flight path was set, and we were approaching the end of the runway. On March 6, 1991, sixteen months after his diagnosis, we huddled close – Mom, my sisters, and me – watching helplessly as Dad took his last breath in the home he had filled with so much fun and love.

I fled downstairs to my bedroom, buried my face in my pillow, and released a lifetime of sobs that would echo in my heart forever.

He was only 51. Mom was 50 years old and had lost the love of her life.

I was 20, and my sister Kimberly was 26 and Heather, 27.

The Farewell

Our church Saint John’s Episcopal Church in McLean, Virginia, overflowed with people who loved Dad as we did. Neither my mom, my sisters or I could speak—the weight of loss left us silent. Thankfully close family and friends did.

As we turned from the front pew, his casket was beside us. I burst into tears, unable to leave him. My heart, my arms, my head laid against the casket, as if my energy had fused with it. I would have let them carry me out with him. Our Aunt Jane had to pull me away.

I can still feel that moment in my chest and all its power today.

At the reception, people called us Rupertus girls strong. Really, we were in shock.

The Final Honors

His funeral brought a clear, cold March morning at Arlington National Cemetery. Six black horses pulled Dad’s flag-draped casket on a caisson, their breath visible in the winter air, hooves clicking solemnly against the pavement. Our family followed the caisson, passing rows of white headstones stretching endlessly over Arlington’s rolling hills.

The Marine Corps Body Bearers—stoic, disciplined, and precise—moved in perfect unison, their white gloves stark against dress blue uniforms. They carried Dad with the dignity he deserved.

At the gravesite, the ritual unfolded with military precision.

The Marines folded the flag—thirteen deliberate folds, each with meaning. Our beloved minister spoke, though his words barely penetrated our grief. Then came the rifle salute—three volleys cutting through the silence, making us jump despite knowing they were coming. A lone bugler played Taps, its mournful notes floating over the hallowed ground.

A Marine knelt before Mom, presenting the folded flag.

“On behalf of the President of the United States, the United States Marine Corps, and a grateful nation, please accept this flag as a symbol of our appreciation for your loved one’s honorable and faithful service.”

Mom received it with grace, though through my tears, I saw her tears.

Here was Dad’s final flight. His last mission.

Complete anguish.

We left him among heroes—his family, and the soldiers, Marines, and sailors who had also answered their country’s call. His final resting place, in Section 60, beneath the shadow of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, has become sacred ground for our family.

A Bond That Never Breaks

A week after his funeral, a manila envelope arrived at our house. Inside were black-and-white glossy photos from Dad’s burial at Arlington. Tucked among them was a note from Lenny, one of Dad’s closest Naval Academy friends—a man who had spent years in the shadows at the CIA.

Thank you Lenny, we never even saw you there. We would have embraced you.

Thirty-four years have passed since that day at Arlington, and I still miss him. Is that crazy? I’ve come to understand that some bonds never break—they only change form. I see Dad in my own square jaw, in the blue eyes, empathy and self competitive spirit I inherited, that have been passed down to my children. I hear him in my head—”Don’t take a lazy man’s load!”—in the moments that demand resilience.

His grave at Arlington is a place of peace I love to visit. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial still stands, reflecting both our past and present. When I visit the family grave, where he, my mom, and his father and more family are buried, I lean back on the headstone, feeling the smooth stone, and connect to their love and perseverance.

I understand now why he needed my sister Kimberly and I there that day at the wall in 1982—not just as witnesses, but as a bridge between his military world and civilian life, between his pain and his hope.

Only later, as I researched my grandfather’s story for Old Breed General, did I fully grasp the weight my father carried. He had built his life not just on resilience, but on service and tenacity—choosing to honor the past by forging ahead.

I only had my father in my life for twenty years … and it took me twenty more years until I would face the grief of losing him. Crazy, I know!

But today, I’m so thankful we had Dad for the years we did, and that he had so many people who loved him.

Dad was more than a Vietnam veteran. More than a Marine. More than a real estate developer who knew how to melt the ice at a table. More than the father who checked for warm TVs and made jokes about “God Damned Civilians.” He was a guardian of memory. A keeper of tradition and stories both told and untold. A man who left a legacy of passion, kindness, and courage.

He taught me that strength isn’t about being better than someone else—it’s about being the best you can be. It’s about facing life with grace, grit, and humor.

For my father, Patrick Hill Rupertus, USNA Class of ‘62— We loved you. We remember. We honor. We heal.

Semper Fidelis.

One Response

Beautiful